Legal Update

Aug 19, 2020

Anatomy of an Earnout in the Era of COVID-19: Best Practices for Designing Earnouts to Avoid Disputes

Sign Up for our COVID-19 Mailing List.

Visit our Beyond COVID-19 Resource Center.

This Legal Update was also published by Business Law Today, the online platform of the Business Law Section of the American Bar Association, which can be read here.

As we write this article mid-summer of 2020, with a resurgence in COVID-19 cases in the South, Southwest, and Western United States, uncertainty caused by the virus abounds, including in the world of M&A transactions. Due to the unpredictability caused by the pandemic, buyers and sellers of companies have less ability to predict the earnings and future performance of the target business. As either Mark Twain or Yogi Berra supposedly said, “it is difficult to make predictions, particularly about the future.”

In this current environment, parties to M&A transactions are likely to use earnouts more frequently. For parties structuring a transaction to deal with future uncertainties caused by the pandemic, earnouts can bridge the valuation gap between buyers and sellers. The purpose of an earnout is to allocate the future risks and rewards of a target business, with both parties benefitting from a successful outcome and sharing the risk if things do not work out as hoped. Earnouts, however, are inherently difficult to design and implement because they require the parties to anticipate what might happen in the future.

Earnouts are often half-jokingly referred to as “litigation magnets.” The high stakes involved means that disputes can get particularly ugly,[1] causing the expenditure of large amounts of time and money in the ensuing litigation. An earnout that has been carefully designed and considered by the parties is worth the upfront effort if it can avoid or allow a dispute to be quickly resolved.

This article brings together the perspectives of two veteran M&A attorneys with a dispute management director at SRS Acquiom. SRS Acquiom brings a wealth of experience since it has served as the seller representative, or in another comparable capacity, in over 2,100 transactions. SRS Acquiom has seen firsthand when earnouts work as intended and when they devolve into difficult-to-resolve disputes. We will take a detailed look at the complex components of a well-structured earnout from our collective experience, and discuss some best practices for designing earnouts to minimize disputes.

Use of Earnouts Before the COVID-19 Pandemic

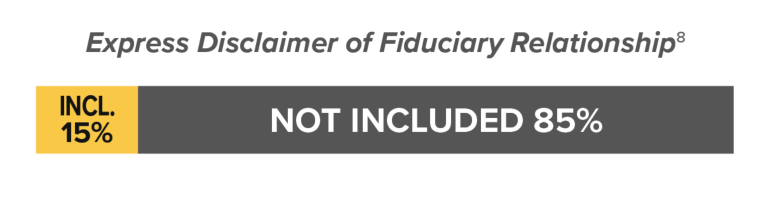

The use of earnouts often differs by industry. Using the MarketStandardTM transaction database of SRS Acquiom, which includes 1,300+ private-target acquisitions from 2015 to date, we compared the use of earnouts in life sciences, technology, and other industries over the past 18 months:

Image description: A chart titled Earnout Included in the SRS Acquiom Database. Life Sciences, 62% included and 38% not included. Technology, 12% included and 89% not included. Other Industries, 23% included 78% not included.

There is a long tradition of earnouts in the life-science industry focusing on regulatory and other specialized milestones that are not generally used for earnouts in technology and other industries. Although there are lessons to be learned from life-science transactions, in this article we focus primarily on using earnouts outside of the life-science industry because life-science transactions are so specialized, and their milestones are not generally used for earnouts in technology and other industries.

Outside of the life-science industry, buyers and sellers are generally more wary of using earnouts. As shown in the chart above, prior to the pandemic, earnouts were used in only a relatively small portion of the transactions[2] to bridge a valuation gap. Due to the uncertainty caused by the pandemic, we expect the use of earnouts to increase across these other industries.

Is an Earnout the Right Tool to Bridge the Valuation Gap?

For some earnout disputes, the root cause of the dispute was that the earnout structure was the wrong way to bridge the valuation gap. As a result, the buyer and seller may have had different expectations for the earnout, and their interests were not aligned after closing. Whether a specific earnout structure is the right tool to bridge the valuation gap begins with an analysis of the following questions:

Will the operations or products of the target business be merged with those of the buyer, or will the business be operated on a stand-alone basis? Earnouts measured on earnings or EBITDA make more sense when the target business will be operated on a stand-alone basis after closing. It is easier to design and track whether the earnings have been achieved during the earnout period when the business is compartmentalized. On the other hand, if the operations of the target business will be merged or otherwise integrated with those of the buyer, earnouts based on earnings become difficult to manage and track because both revenues and expenses must be determined. When the acquired business operations are merged with the buyer, an earnout based only on revenues may be more appropriate. Even then, however, if the products or services of the target company are sold as a “bundle” or otherwise combined with the products or services of the buyer, revenues specific to the sold business may be difficult to determine with objective certainty.

Will the management team of the seller continue working for the buyer, and if so, will the goals of the earnout align with the roles and authority assigned to the management team? If the seller’s management team will not be working for the buyer, or will have no real influence over the buyer’s operations and decision making after closing, the seller may not have faith that the buyer will be sufficiently focused on or motivated to achieve the earnout. The seller or its representative may find it challenging to adequately monitor earnout progress absent former management’s ongoing and direct role in managing the business. The reality is that even robust milestone reporting requirements may not tell the full story.

If the seller’s management team will continue working for the buyer, does the management team have a significant equity stake in the seller so that the management team will enjoy a meaningful amount of the earnout? In many technology companies, the founders and the management team may have been diluted over multiple funding rounds and own a relatively small equity stake in the target business. Similarly, in many private equity portfolio companies, the management team may have a small amount of equity. In these situations, the management team may not have a sufficiently large interest in the earnout to have a compelling incentive to achieve it. Instead, the seller’s management team may have business objectives and compensation incentives after closing that are different from those of the earnout.

The answers to these questions may lead to the conclusion that an earnout is the wrong approach. Too often, the parties do not pay enough attention to whether an earnout works in the particular circumstances of a specific transaction—in essence “kicking the can down the road” on valuation. If the buyer and seller have different expectations on whether and how the earnout will be achieved, the result can lead to a costly dispute.

Particularly, if an earnout is a significant portion of the consideration for a transaction, the seller must recognize the inherent risks involved with an earnout. It can be difficult and expensive to challenge an unfavorable earnout report even with seller-favorable earnout terms.

What Is the Right Metric to Use for an Earnout?

Determining the right earnout metric begins with an analysis of the methodology used by the buyer to value the target business, and whether that methodology is appropriate to measure the business during an earnout period. Three common ways to value target companies are:

- multiple of prior 12 months of EBITDA, which is used for companies with earnings (this is the most common valuation methodology);

- multiple of revenues, most commonly used for software and other technology companies that have been able to build significant sales but are not at the stage of having earnings; and

- a “build versus buy” analysis, in which the buyer assesses the cost to duplicate the functionality of the seller’s product or technology from scratch, versus the cost to buy the seller and its entire workforce (this measure is most commonly used for early-stage software and other technology companies prior to achieving significant sales revenues).

Generally speaking, the valuation methodology used to value the business begins the discussion for the earnout metric that will be used. If a multiple of EBITDA was used to value the business, then an increase in EBITDA is a logical place to begin. The same for revenues. When a “build versus buy” methodology is used, then neither EBITDA nor revenue measures may fit the situation. In any event, the choice of the earnout metric will require a much deeper analysis of the value that the buyer is trying to create by buying the target business, and the buyer’s business plan to create this value after closing.

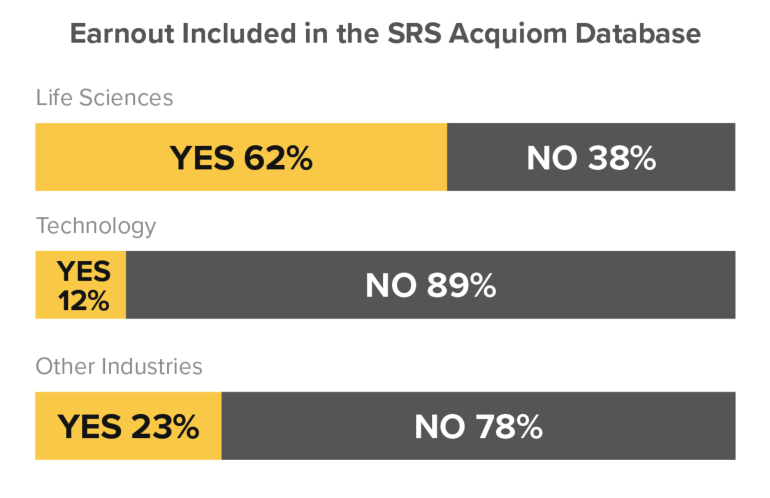

Using the SRS Acquiom MarketStandardTM transaction database, for nonlife-science transactions over the past 18 months, the most common metrics for earnouts are shown below:[3]

Image description: A chart titled Earnout Metrics. Revenue, 65%; Earnings, 17%; Regulatory Milestone, 2%; Other, 33%.

Before the pandemic, we were in a seller’s market with auctions of quality companies attracting numerous bidders so that sellers could obtain high prices and favorable terms. Sellers generally prefer using revenues as a metric because revenues do not include costs and expenses and are easier to measure with less ability for the buyer to skew the results. On the other hand, buyers favor using EBITDA as a metric, which includes costs and expenses, because EBITDA is generally used to gauge a company’s true operating performance and to value a business for sale. If we shift to a buyer’s market after the pandemic, we can expect more earnouts based upon EBITDA, or a combination of EBITDA and revenues, than in the past.

Nonrevenue/EBITDA metrics are common in life-science deals where the value of a target company may be based in substantial part on the future of a particular drug. For life-science deals, revenues and regulatory milestones are the most common metrics used for earnouts, or some combination, and earnings are rarely used.[4]

Outside of life-science deals, SRS Acquiom has seen some increased use of project-based or other nonrevenue/EBITDA metrics—sometimes in conjunction with these traditional approaches. The COVID-19 pandemic will likely continue to have unpredictable effects on revenue and EBITDA, so sellers and buyers should be open to other approaches for earnouts. SRS Acquiom has seen an interesting range of nonrevenue/EBITDA metrics used in conjunction with revenue and/or EBITDA, which include the following:

- Project-based metrics providing for a payment if a certain discrete project is brought to completion. For software companies, this may mean bringing a certain product or product version to market. Obviously, the success parameters and resources to be dedicated to the project must be carefully defined.

- Sales-based earnouts where a specific number of product units must be sold.

- Earnouts tied to store openings in response to the COVID-19 crisis. This approach essentially shifts the risk to the sellers if the pandemic continues to impede retail operations.

What Are Best Practices for Defining the Metric in the Purchase Agreement?

The answer to this question can be best summed up as follows: (i) be as specific as possible, (ii) use objective measures that lend themselves to outside standards of measurement by third parties, and (iii) use illustrative examples whenever possible.

For nonrevenue/EBITDA metrics, the parties must be as specific as possible when describing the milestone, whether a milestone has been achieved, and the deadlines for achieving each milestone. Parties might use commonly used terms to describe a milestone, but fail to take into account the differing interpretations of those terms if a dispute arises years later or if unexpected scenarios arise.

For EBITDA, the definition of “EBITDA” can be complex, and it is becoming more common to define “Adjusted EBITDA”—with sometimes detailed specifications for how EBITDA is being adjusted. The analysis requires the parties to review each line item of the income statement of the target business to determine whether the specific line item will be included in the calculation of EBITDA for purposes of the earnout. The analysis also requires the parties to think about possible types of revenues or expenses that would be unfair to include in the calculation, such as gains or losses from the sale of capital assets, gains or losses caused by a change in accounting policies, and gains or losses caused by one-time events outside of the ordinary course of business. For example, if the target business has a loan under the Paycheck Protection Program, the parties will want to specify that forgiveness of the loan does not factor into the EBITDA calculation. A particularly difficult area is to determine how any shared expenses—such as insurance or other overhead—will be allocated between the target business and the rest of the buyer’s business.

It can be helpful to provide a sample EBITDA calculation as an exhibit to the purchase agreement using prior financial statements showing how EBITDA was calculated and how it will be calculated for the earnout calculation. This is commonly done for other financial metrics such as net working capital and the components of what constitutes working capital in a particular transaction. It becomes more difficult, however, if the acquired business will be integrated into a larger, possibly more sophisticated business, and the accounting will be changed to conform to the accounting practices of the buyer. In that case, it is helpful to prepare a sample template using the buyer’s accounting practices to show how EBITDA will be calculated and attach that template as an exhibit to the purchase agreement.

For a financial metric such as EBITDA, the next issue is the proper accounting principles. If the target business has audited financial statements prepared in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), then a typical definition of the “Accounting Policies” in a purchase agreement would be: “GAAP, applied using the same accounting principles and standards, policies, procedures and classifications used by the Company in preparing the Audited Balance Sheet.” What if there is a conflict between GAAP and the methodologies used by the Company in preparing the Audited Balance Sheet? It helps to have a controlling statement in the definition to provide which one will control if there is a conflict. This also applies if there is an accounting term specifically defined in the purchase agreement that differs from GAAP—it helps to have a controlling statement within the definition of “Accounting Policies” to provide that the defined term will control if there is a conflict with GAAP.

Conflicts also can arise when a target business is a relatively small business being acquired by a much larger company with more rigorous accounting practices. Even if the small target company has audited financial statements prepared in accordance with GAAP, there can be differing interpretations of GAAP and different policies, such as the determination of “materiality.” Accordingly, it helps if those differences in how GAAP is applied by the seller and the buyer are identified during due diligence so they can be properly dealt with in the purchase agreement definitions of the applicable accounting policies and other financial terms used for the earnout.

Another challenge is that smaller companies may not have GAAP-based financial statements, and may instead use the cash basis of accounting, the tax basis of accounting, or some hybrid. For an earnout, especially if the buyer uses GAAP, it is important to determine how the financial statements of the target business and the buyer differ, and how the earnout metrics will be determined by the buyer. In this situation, it is helpful to attach a template as an exhibit to the purchase agreement showing how EBITDA or any other metric will be calculated for purposes of the earnout.

How Else Do You Structure an Earnout to Achieve the Right Result?

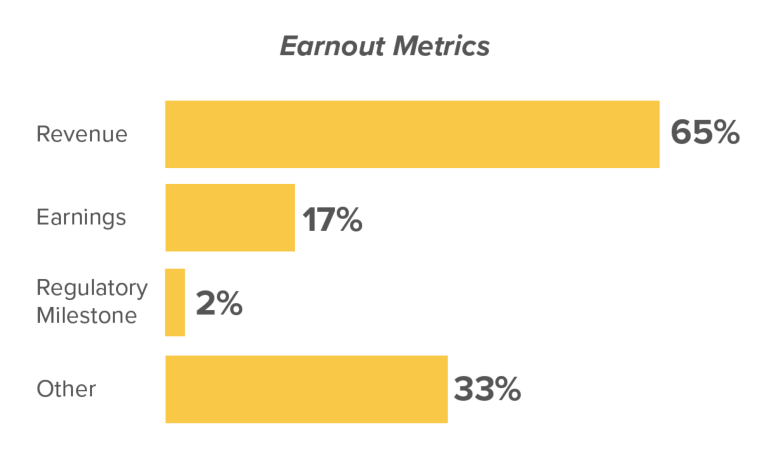

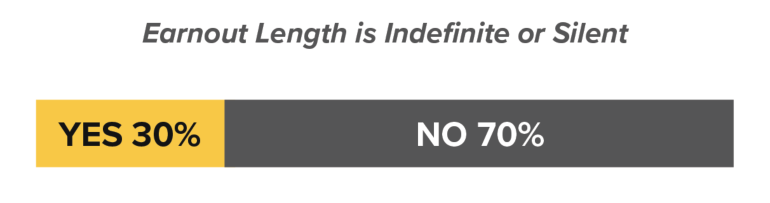

Using the SRS Acquiom MarketStandardTM transaction database, for nonlife-science transactions over the past 18 months, the earnout time periods are set forth below. Interestingly, there is a slight trend toward earnout length that is indefinite or does not expire, particularly with nonfinancial or other milestones. The lack of a deadline can remove a frequent source of dispute: whether the milestone was timely achieved, or would have been timely achieved but for some act or omission of the buyer.

Image description: A chart titled Earnout Length. 1 year or less, 46%; greater than 1 year to 2 years, 14%; greater than 2 years to 3 years, 11%; greater than 3 years to 4 years, 14%; greater than 4 years to 5 years, 3%; greater than 5 years, 11%.

Image description: A chart titled Earnout Length is Indefinite or Silent. Yes, 30%; No, 70%.

Prior to the pandemic, parties generally wanted the earnout period to be as short as possible. As a result of post-pandemic uncertainty, the time period for earnouts will likely increase from the current median of 24 months to longer timeframes. Given the unpredictability of how long it will take for businesses to recover from the pandemic, most companies have no visibility into what their results will be for 2020, and even into 2021. Therefore, earnout periods may extend into 2022, 2023, and beyond to give the seller more opportunity to achieve the earnout. When the earnout period increases, this places more burden on the buyer to manage and track the earnout throughout the longer timeframe. It also increases the risks that unexpected circumstances and events will occur that affect the business and restrict the buyer’s ability to make needed changes that could potentially affect the earnout, such as merging the business with other operations of the buyer.

According to the 2020 M&A Deal Terms Study published by SRS Acquiom, in nonlife-science transactions with earnouts, the earnout potential as a percentage of the closing payment averaged 30% in 2018 and 41% in 2019, although the median was likely significantly lower, given that some outlier transactions pulled the average up. Due to the changed environment after the pandemic, the earnout potential as a percentage of the closing payment may increase from the 41% in 2019 shown in the SRS Acquiom data to 50% or higher. By doing so, buyers will shift more of the uncertainty and risk caused by the pandemic to sellers. In turn, as the size of the earnout potential increases, there is more incentive for the seller to challenge the buyer over whether the earnout has been achieved. This leads to the next structural issue of whether the earnout should be structured as “all or none” or on a sliding scale.

It is an open question whether the sliding scale may lead to more earnout disputes. When an “all or nothing” threshold applies, it is frequently clear to both seller and buyer whether the earnout metric was achieved. A disagreement becomes a formal dispute only when it will make the difference between all and nothing. If the sliding scale applies, however, the disagreement may trigger a dispute at each stage if the disagreement is material. One recent SRS Acquiom matter illustrates this dynamic. It was unclear from the earnout provision whether a specific type of customer refund should be included as revenue. The disagreement over how to interpret the provision likely would not have mattered in an “all or nothing” structure. Given that a sliding scale applied, however, the difference was sufficiently material for the parties to engage counsel and escalate to a formal dispute.

One countervailing business argument for using a sliding scale, however, is that the “all or none” structure can be demoralizing to the seller’s management team (now working for the buyer) if it becomes clear that the earnout will not be achieved, and the sliding scale would maintain the incentive. Further, use of the sliding scale could reduce the amount subject to a dispute. If a sliding scale is used, it is important to use a floor and a cap to fence in the amount of the earnout payment.

That said, when an earnout is small relative to the size of the transaction, say 10%–15% as a percentage of the closing payment, and is based on EBITDA or revenue, it is not as important whether the earnout is structured with an “all or none” threshold in which the threshold must be reached to receive any portion of the earnout. For example, if the original purchase price was justified based on a sales run rate projected by the seller that now seems questionable, the buyer may request that the earnout be paid only if the sales are actually achieved.

When the earnout potential becomes a larger portion of the total consideration, and the earnout period is longer, the parties must focus on dividing up the earnout period in shorter intervals, and providing for partial payments for each earnout period. For example, for a deal closed today, the parties could set the earnout periods as calendar years 2021 and 2022, with a portion of the earnout paid for each period based on the percentage of the earnout goal that was achieved. When a sliding scale is used, this reduces the incentive to the buyer to try to skew the results if the earnout has an “all or none” threshold and the results are close to the threshold. With the uncertainty caused by the pandemic for 2020, some parties are starting the earnout period in 2021 with the thought that earnings for 2020 will not be an accurate measure of future earnings. Further, parties using partial payments for different earnout intervals may want to allow for catch-up payments if the earnout was not achieved during the initial periods, but was caught up in the final earnout period when measured over the entire earnout period.[5]

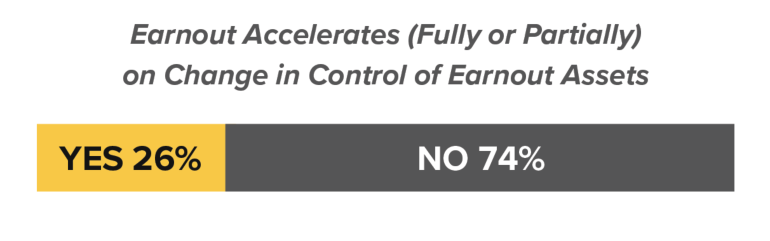

Another issue that may arise with an increase in earnouts is determining what happens to the earnout if the buyer is acquired during the earnout period. Should the earnout accelerate upon the buyer’s change of control, or continue in effect? Using the SRS Acquiom MarketStandardTM transaction database, for nonlife-science transactions over the past 18 months, the graph below shows the percentage of transactions that accelerate the earnout payment upon a change of control.[6]

Image description: A chart titled Earnout Accelerates (Fully or Partially) on Change in Control of Earnout Assets. Yes, 26%; No, 74%.

The size of the buyer relative to the size of the target business is a big factor in whether the earnout should accelerate upon a change of control of the buyer. If the target business is a large portion of the buyer’s overall business, then the sellers have a strong argument that the change of control should trigger the earnout acceleration. On the other hand, if the buyer is substantially larger than the target business, the earnout is less likely to contain an acceleration upon a change of control. In either case, the purchase agreement should specify what happens to the earnout upon a change of control rather than leaving this silent.

In the right circumstances, the parties may consider including a buyout provision under which the buyer can pay a fixed sum, or use a different metric and time period to buy out and terminate the earnout. This can be especially helpful if the buyer believes there is a reasonable possibility that the buyer could be acquired during the earnout period and would not want the earnout to impede the sale of the buyer.

What Covenants Are Appropriate for Operating the Target Business after Closing with Respect to the Earnout?

Buyers and sellers will often vigorously negotiate whether there should be controls or other constraints on how the buyer operates the purchased business during the earnout period. Buyers naturally do not want any constraints; they argue that they need full discretion to run the business to deal with rapidly changing business conditions, such as what we are seeing right now with the pandemic. Sellers, however, want a fair shot at being able to earn the earnout, especially if the management team of the seller goes to work for the buyer. Many times, “soft” promises will be made to the seller for the financial support or other resources that the buyer will provide to the business after closing so that the earnout can be achieved, but those “soft” promises never make it into the purchase agreement and are generally unenforceable. The natural tension between the seller and the buyer over the buyer’s business decisions will be exacerbated if the earnout period is long.

The Standard Operating Covenants

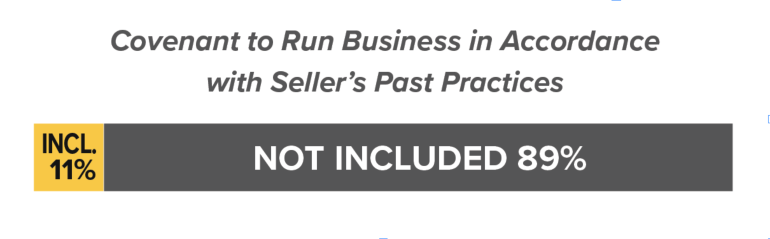

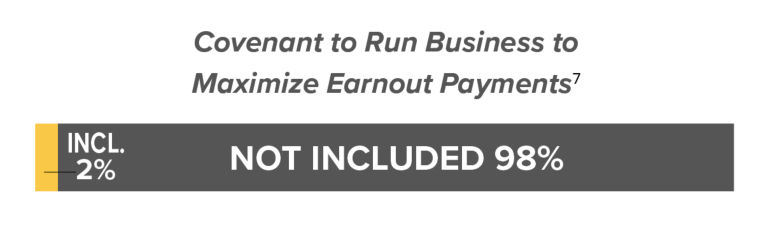

Using the SRS Acquiom MarketStandardTM transaction database, for nonlife-science transactions over the past 18 months, parties used some of the following covenants in purchase agreements in the percentages described below:

Image description: A chart titled Covenant to Run Business in Accordance with Seller's Past Practices. Included, 11%; Not Included, 89%.

Image description: A chart titled Covenant to Run Business to Maximize Earnout Payments. Included, 2%; Not Included, 98%.

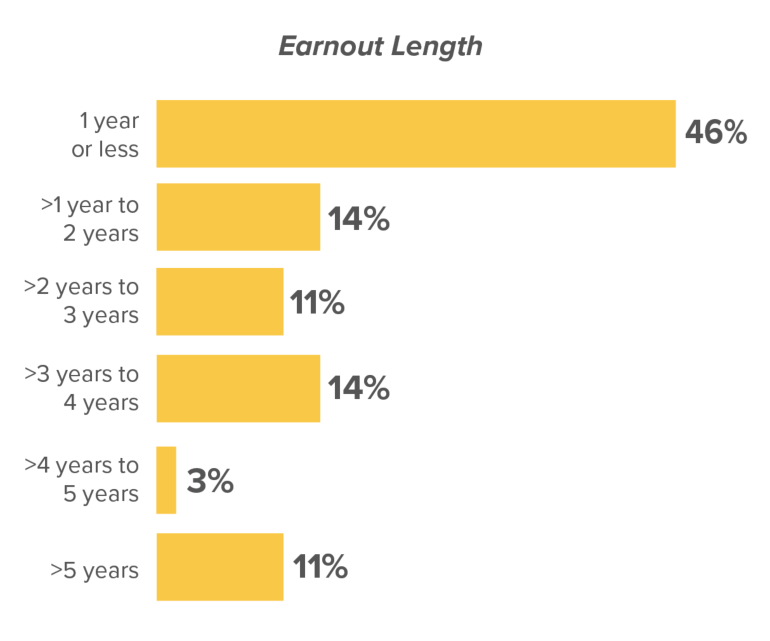

Image description: A chart titled Express Disclaimer of Fiduciary Relationship. Included, 15%; Not Included, 85%.

Sellers often push for a covenant that the buyer will operate the purchased business in accordance with seller’s past practices. When sellers have a lot of leverage, they will request a covenant that the buyer will operate the business to maximize earnout payments. Although these types of covenants are sometimes agreed to by the parties to get the deal done, they must recognize the potential difficulties they are causing by using these covenants. It may not be entirely clear what the parties mean with these covenants. Many times, the buyer and seller have very different interpretations of these covenants. For the covenant to run the business in accordance with seller’s past practices, in a dispute the seller must create a factual record of how the seller operated the business prior to closing and then demonstrate that the buyer failed to do so during the earnout period.[9] If the buyer is dealing with pandemic fallout, perhaps by drastically reducing expenses due to lower customer demand, certain actions by the buyer may be prudent, but not consistent with seller’s past practices.

If the earnout period is long, buyers will be uncomfortable agreeing to any covenants that restrict their ability to run the business. Buyers will want to have a statement affirming that the buyer has full discretion to direct the management, strategy and operations of the purchased business. If buyers have negotiating leverage, they may also request a statement expressly disclaiming any fiduciary duties to the seller with respect to the earnout. This is an attempt to avoid a seller’s claim that the buyer did not abide by any implied duty of good faith with respect to the earnout. Even if the purchase agreement is silent regarding fiduciary duties, Delaware courts impose a high threshold for a seller to prevail on a claim based on an implied duty of good faith.

Although not tracked by the SRS Acquiom data, it is more common for buyers to agree to a negative covenant that the buyer will not take actions in bad faith that would reasonably be expected to materially reduce the amount of the earnout. The parties will sometimes agree to an affirmative covenant for the buyer to operate the business in a commercially reasonable manner as a middle ground compromise, but in a dispute, this type of covenant is so vague that it can be difficult to base a claim on it without a more specific definition or particularly egregious facts. Sellers should keep in mind that the gray areas created by ambiguous language like “commercially reasonable manner” may work to the buyer’s advantage because the buyer can, if challenged, provide an after-the-fact rationale to its actions. The more specific the definition, the more likely these issues can be avoided or at least mitigated. For example, the parties can combine a general “commercially reasonable efforts” clause with a more specific operating covenant.

Using specific operating covenants. Where possible and appropriate, sellers should seek to establish specific negative and affirmative operating covenants, especially where those covenants are core to the ability to achieve the earnout. For example, examples of affirmative covenants are:

- providing funds for specific capital expenditures;

- allowing the business to hire additional employees for specific purposes, such as engineers, software developers, or sales staff;

- providing resources from the buyer’s corporate staff or other business units for specific purposes, such as marketing, sales advertising spend, use of the buyer’s social media accounts to promote the business, or cross-promotion from the buyer’s other products to support the sales of the products of the purchased business; and

- operating the purchased business on a standalone basis, with financial statements maintained on a separate basis.

Examples of negative operating covenants are:

- allocating corporate overhead in a disproportionate manner;

- making major changes to the business, such as combining other business units with the purchased business or selling material assets;

- materially decreasing management or employees; and

- combining products or services of the buyer with those of the purchased business.

One covenant that SRS Acquiom has found invaluable for minimizing disputes is the obligation of the parties to negotiate in good faith if there is a material change in circumstances that potentially frustrates the earnout. This obligation motivates the parties to work collaboratively to achieve the desired outcome for the buyer and secure at least a portion of the earnout for the seller.

How Do You Determine Whether the Earnout Metric Has Been Achieved?

Earnouts require sellers to have a certain degree of trust, or at least faith, in the buyer’s good intentions, but as former President Reagan famously held: “Trust, but verify.”

- Earnout reporting requirements must be specific and precise, and provided to the seller on a regular basis. This is especially important if seller’s management is no longer working for the buyer. If former owners are still working with the purchased business after the closing, the seller representative normally works closely with those former owners who act as its eyes and ears. Absent such inside access and knowledge, it can be difficult to challenge an unfavorable earnout report because the buyer controls the facts and the business records.

- The purchase agreement should include broad rights to examine business records and documents and to interview seller’s employees who are now working for the buyer. These rights will allow the seller representative to thoroughly examine an unfavorable earnout report. The mere existence of these rights in the purchase agreement and the request to interview employees can create an incentive for the buyer to act appropriately.

- In its role as seller’s representative, SRS Acquiom has accountants on staff who will review the earnout report and supporting documentation to look for indications that items are not reported consistent with the agreed-to accounting policies or not reported in the same manner that existed pre-closing.

- The right to an audit, however, is less important to sellers than one might think. Normally, disputes arise from operating decisions made by the buyer after closing that led to the unfavorable financial outcome, rather than any actions by the buyer to unfavorably manipulate the financial results.

What Are Best Practices for the Dispute Resolution Provisions Involving an Earnout?

Perhaps more than any other part of the purchase agreement, the earnout provisions require careful attention by the parties and their respective counsel. Delaware courts will strictly review the earnout provisions and apply the plain meaning of the wording. Further, as mentioned above, Delaware courts will only rarely find that the implied covenant of fair dealing was breached and regularly admonish parties that they had full opportunities to negotiate the specific terms of the agreement, and should therefore not ask the courts to add terms or duties that the parties could have negotiated beforehand.

SRS Acquiom, in its role of seller’s representative, generally likes to see the following provisions in the dispute resolution section of the purchase agreement:

- Choice of law. Many M&A transactions are governed by Delaware law, and this is particularly the case when earnouts are included. Given that so many M&A disputes are governed by Delaware law, there is well-developed and robust case law for earnouts that may provide guidance on the legal analysis and thereby help to resolve disputes without having to resort to litigation. If laws of another jurisdiction are used, it is important to understand how the case law of the other jurisdiction may differ from Delaware. For example, unlike Delaware law, case law in certain states may impose an implied duty to operate the business in a manner to achieve the earnout.

- Venue. Assuming Delaware law is used, SRS Acquiom strongly prefers exclusive venue in the Delaware Court of Chancery. The Chancery Court judges are often experienced business lawyers who are familiar with M&A transactions and have prior experience with earnouts. Disputes in Chancery Court get to trial faster than courts in other jurisdictions (including Delaware Superior or Federal Courts), which reduces the costs and stresses of litigation. There is also no jury in Chancery Court, which leads to shorter and therefore less expensive trials. In contrast, when earnout disputes end up in courts outside of Chancery Court, there is a risk that the judge, no matter how experienced in other matters, may be unfamiliar with M&A transactions generally and have no prior experience with earnouts. If the case goes to trial before a jury, the jury almost certainly will be unfamiliar with M&A. If any venue other than the Delaware Chancery Court is specified, it is advisable to include a waiver of trial by jury.

- Resolution by accounting firm versus a court. Earnout provisions may provide for an accounting firm to resolve any dispute relating to the earnout. This stems from a belief by the parties that, just like a working capital adjustment, an earnout determination will be based on GAAP or the accounting policies that an accountant should be able to determine. In this situation, it may be unclear whether the accounting firm is acting as an accounting expert to determine the proper application of GAAP or other accounting policies, or as an arbitrator with a much broader mandate to resolve any other issues.

In the experience of SRS Acquiom, however, the proper application of GAAP or other accounting policy is rarely the sole reason for the dispute, but instead frequently involves the buyer’s underlying business decisions and whether those business decisions breached the earnout covenants. The earnout issues may be too broad and complex for an accounting firm to arbitrate, especially when the potential earnout is a large portion of the total purchase price. Although accounting arbitration can be valuable to resolve disputes over a small earnout or working capital when less is at stake, a seller on the short end of a potentially large earnout will likely file a lawsuit anyway if it suspects the buyer made inappropriate operational decisions that caused the shortfall. A particularly bad outcome is when the buyer drives up the cost by forcing a portion of the dispute into accounting arbitration while other issues are fought in a parallel litigation or traditional arbitration.

If the earnout is a large percentage of the purchase price, SRS Acquiom prefers to see the earnout dispute resolved in the Delaware Court of Chancery, with a waiver of jury trial. Traditional arbitration through AAA, JAMS, or other similar third-party arbitrator not limited to accounting issues also can be effective if the parties are particularly sensitive about keeping the dispute confidential, but based on the prior experience of SRS Acquiom, it typically does not save time or money over the Delaware Chancery Court.

- Prevailing-party fees. Earnout disputes can be expensive to resolve. The parties should consider a provision in the purchase agreement that allows attorney’s fees to be awarded to the prevailing party in a dispute, and that provides for payment of interest on a wrongfully denied earnout payment. SRS Acquiom believes these provisions can motivate parties to resolve earnout disputes before resorting to litigation.

There is no single playbook for resolving disputes, which often depend on the type of earnout at issue and what resources the buyer and seller have available. Given that earnout disputes can be expensive, sellers must ensure that the expense fund available to the seller’s representative is sufficient to allow it to properly review the earnout report and contest the findings if necessary.

Earnouts can help buyers and sellers in the current environment creatively bridge a valuation gap between them and allocate the risks of future performance. Although earnouts can be difficult to design and implement because they require the parties to anticipate future events that are inherently uncertain, careful thought by the parties and implementing best practices can help them achieve their respective goals for the transaction and minimize the possibility of a future dispute.

[1] One of the authors reviewed the pleadings of a lawsuit in New York state court over an earnout in which none of the authors were involved. The lawsuit between two private equity firms over an $8 million earnout consumed over seven years of highly acrimonious fighting between the parties, with no doubt millions of dollars of legal fees spent by the parties.

[2] The percentages of transactions with earnouts was somewhat higher in the 2019 Private Target Mergers and Acquisitions Deal Points Study published by the Business Law Section of the American Bar Association in December 2019 (ABA 2019 Deal Terms Study), which included transactions through the first quarter of 2019. This study uses only publicly available purchase agreements filed by public companies on the Edgar website of the Securities and Exchange Commission. This study showed that earnouts were used in approximately 27% of transactions occurring from 2016 to the first quarter of 2019.

[3] The ABA 2019 Deal Terms Study had a more even split between revenue and earnings as the metric, with the earnouts for 2018–1Q 2019 transactions being based 29% on revenues and 31% on earnings. This may be due to the SRS Acquiom database of transactions more weighted toward technology companies, which are more likely to use revenue for earnouts versus the more varied group of only public companies in the ABA 2019 Deal Terms Study.

[4] Using the SRS Acquiom MarketStandardTM transaction database, for life-science transactions over the past 36 months, the most common metrics were revenue (69%), earnings (8%), regulatory milestone (53%), and other (47%). The 2020 SRS Acquiom M&A Deal Terms Study, powered by MarketStandard, analyzes more than 1,200 private-target acquisitions, valued at over $239 billion that closed from 2015 through 2019 in which SRS Acquiom provided professional and financial services. To view or download the study, go to: https://www.srsacquiom.com/resources/2020-ma-deal-terms-study/.

[5] An example of this structure was used in a recent transaction announced June 22, 2020, involving a public company, LeMaitre Vascular, Inc. (Nasdaq: LMAT), in which the purchase agreement was filed with the SEC. In this transaction, the earnout was structured with three earnout periods in calendar years 2021, 2022, and 2023 based on a specified number of units of product sold during each period, using an “all or none” threshold during each period. After the final earnout period in 2023, however, the purchase agreement provided for a catch-up payment based on a sliding scale if the aggregate number of units sold exceeded a minimum threshold. As a result, even if the seller missed the earnout thresholds in 2021, 2022, and 2023, the seller could still receive a partial catch-up earnout payment based on the overall performance over the entire three-year earnout period. None of the authors was involved with this transaction.

[6] The percentage of transactions in the ABA 2019 Deal Terms Study that accelerated upon a change of control was 22% for 2018–1Q 2019 transactions, which is consistent with the SRS Acquiom data.

[7] The ABA 2019 Deal Terms Study had the following for these two covenants:

- covenant to run business consistent with past practice—10% for deals in 2018–1Q 2019, which is consistent with the SRS Acquiom data; and

- covenant to run business to maximize earnout—17% for deals in 2018–1Q 2019, which is much higher than the SRS Acquiom data.

[8] The ABA 2019 Deal Terms Study showed 15% of deals in 2018–1Q 2019 had an express disclaimer of fiduciary relationship, which is the same as the SRS Acquiom data. In addition, the ABA 2019 Deal Terms Study had a corollary statement in 29% of deals in 2018–1Q 2019 that the buyer had discretion for how to operate the target business after closing.

[9] In Edinburgh Holdings, Inc. v. Education Affiliates, Inc. (DE Chancery Court June 6, 2018), Vice Chancellor Slights refused to grant a motion to dismiss based on a covenant that the buyer conduct “activities in a reasonable manner consistent with its past practices.” He stated that the question of whether operations were conducted consistent with past practices was fact intensive and required the court to consider evidence of past practices and compare those practices to those employed by the buyer post-closing.